The Suir and it’s tributaries were also critical to the milling industry, as the power to drive the machinery came from the water-powered millwheels. Dams, millponds and sluice gates were constructed to ensure a constant flow of water to power these millwheels. Most of the mills were flour mills but there were also some cotton mills.

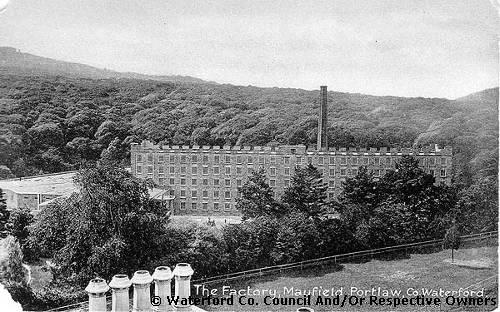

By far the largest mill in Ireland was the Malcolmson cotton mill on the river Clodiagh at Portlaw, Co. Waterford, some eight miles east of Carrick-on-suir. David Malcolmson started out with nothing but ambition, brains and determination. He was a member of the Society of Friends and a Carrick based flour miller. He established the cotton-spinning mill on what was essentially a green field site at Portlaw, County Waterford in 1825. When the factory was completed it measured 260ft by 40ft and was considered the largest single span building in the world. It is said that there were 365 windows in the cotton factory.

This was the greatest factory of its kind in Europe. David Malcolmson employed over 1,500 people at the mill, a fantastic number in those days. By 1840, the factory was bleaching, dying, printing, spinning and weaving cotton and exporting it all over the world. The original village of Portlaw in the 1820s was a group of about 70 cabins. Improved housing was essential to the continued success of a factory in this area. With the factory in production, the Malcolmsons, and their manager, Robert Shaw, methodically re-planned the village of Portlaw. Houses of a very distinctive type were built for the workers to be let at a low rent. The factory town was laid out in the shape of a hand or rays of the sun.

The Malcolmson’s Cotton Mill at Portlaw, Co. Waterford

The Malcolmson designed village of Portlaw, Co. Waterford

In 1837, David handed over the running of his business to his seven sons and from that time they were known as Malcolmson Bros. After his father’s death, Joseph became head of the firm. The Neptune ironworks at Waterford was founded in 1844, mainly as a repair depot for the Malcolmson Bros. ships, but later they went into shipbuilding themselves. The first ship to come off the stocks in 1846 was appropriately named “Neptune” and was built for the St. Petersburg Steamship Co. owned by Joseph Malcolmson. Between 1846 and 1880 a total of 63 ships were built at the yards. Another ‘Neptune’ ship the Una, was one of the first ships to sail through the Suez Canal when it was opened in 1869. The Malcolmson family were also involved in a labyrinth of business enterprises which included corn mills and warehouses at Clonmel, Carrick and Waterford, the cotton spinning factory at Portlaw, the Neptune Ironworks at Waterford, the Cork and Waterford Steamship Co., the St. Petersburg Steamship Co., the Shannon Fishery Co., the Shannon estuary trade at flax weir, Limerick, the Thurles, Limerick, Foynes and Waterford to Limerick railways and the Annoholty Peat Works, near Castleconnell. They held controlling shares in the Shamrock & Hibernia Co. in the Ruhr. The Malcolmsons also had a tea plantation in Ceylon and a teashop on the quay in Waterford.

After the Bank Act of 1846, the Malcolmsons got permission to issue their own “token money” though it had been in use since about 1832. It was legal tender within a radius of thirty miles. Unfortunately, happenings outside the control of the Malcolmson Brothers undermined their future operations. The great famine that swept through Ireland in the 1840’s decimated the peasants and farmers and killed off the supply of grain to the mills. David died in 1846 and his son Joseph who then took over the firm died in 1858. The American civil war in 1861-1865 was a bad blow to the factory. Raw cotton supplies dried-up as Lincoln enforced a naval blockade which affected the Malcolmson ships. They supplied cotton to the southern states, allowing a huge bill to mount up by the losing side. Cotton exports, which totalled £40 million in 1860, fell to £8 million in 1861. It was about that time that the Malcolmsons embarked on a frenzy of house building. All the houses were fine examples of Victorian architecture. Among which was the “Villa Marina” in Dunmore East built as a summer home for Joseph and his wife, “Minella” at Clonmel and “Woodlock House” in Portlaw which was bequeathed, in accordance with Emily Maud’s wishes to the sisters of St. Joseph of Cluny, who turned it into a rest home for the elderly.

When Joseph died in 1858 it was a double tragedy for the firm, as his widow, Charlotte withdrew her share along with other members of the family. Then David died of intemperance at the early age of 37 and left one child, Joseph, who was 7 years old. David’s wife, Nanny Malcolmson, began court proceedings to have her sons share also withdrawn. The crash of the city of London bankers, Overend & Gurney in 1866 was another bad blow for Malcolmsons as they had most of their money invested through that bank, and so suffered a terminal financial blow. The business battled on for some years but in 1877 the Malcolmson Brothers company was declared bankrupt with debts of over half a million pounds and their enterprises were sold off one by one. Sadly it was the end of the line for Portlaw.

The Malcolmsons will also be remembered in Tramore, where in the 1860’s William was involved in constructing the Malcolmson Bank – a feat of engineering which cut off the waters of the Rhine Shark from a portion of the land at the rear of the strand. 263 acres were reclaimed and a fine racecourse was built. With age and neglect of repair, one winter’s storm in 1912 ended a lifetime’s work and flooded the racecourse forever. Nanny Malcolmson retired to Villa Marina in Dunmore East, which she had built as a summer home with her husband Joseph; their son became a dedicated fisherman. Unfortunately, he died at Portlaw before he was 20. In his memory, his mother built the Fisherman’s Hall in Dunmore East and inaugurated a trust fund to help the needy within a three-mile radius of Dunmore. This trust fund is still in operation in Dunmore East to-day.

The factory at Portlaw later became the headquarters of Irish Leathers while the cotton mill in Carrick became the headquarters of Plunder & Pollock which was one on the companies that was later to be the main factory which formed Irish Leathers.

“Villa Marina” built by the Malcolmsons in Dunmore East now the Haven Hotel

Minella Hotel, Clonmel, another Malcolmson Home

The middle half of the 18th century would have been a very depressed period for Irish agriculture with little opportunity for progress in the corn milling industry. During this period Irish farmers increased the area under pasture at the expense of tillage12. This was due to the low cost of production together with the high price of meat and butter. Much of the output was exported. Waterford was one of the major export ports and it may be at this time that the Dowleys first became involved in the river trade.

In 1758 the Irish Parliament made its first real effort to promote tillage. In this year the first bounties were granted for the inland carriage of corn to Dublin, and this seems to have had some effect in checking the influx of British corn into Ireland. In 1767, a small bounty was given by the Irish Parliament on the carriage of Irish corn by sea to Dublin. This further promoted tillage in Ireland. At the same time the English population was rising due to the industrial revolution with a consequent increase in the demand for grain accompanied by a decline in imports from the UK. Towards the end of the 18th century ‘Fosters Corn Laws’ were passed and much attention was focussed on the promotion of tillage. The Napoleonic wars of 1793-1815 also increased the demand for grain.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the British Conservative Party was largely controlled by the landed gentry or aristocrats of the day. They were large producers of grain and the British Corn Laws of 1815-1846 were designed to protect local grain farmers from foreign competition. The Act of Union of 1801 had the effect of extending these laws to Ireland. The laws not only kept prices high; they protected against falling prices in years of plenty. At the time that John Dowley of Tinvane was born in 1810 the grain business was becoming more developed in Ireland. This coupled with the industrial revolution and the population explosion in England gave Irish agriculture an artificial stimulus. Ireland became England’s supplementary granary. The export of wheat and other types of corn from Ireland continued until well after the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 as the corn growing farmer had no other means of acquiring the money with which to meet his rent and other liabilities.

The industrial revolution in Britain in the early 19th century put pressure on the Conservative government to repeal the Corn Laws to provide cheaper bread for the increasing number of factory workers. This pressure kept mounting until it reached breaking point at the beginning of the Great Famine in Ireland. As a result the Corn Laws were repealed in 1846. This had a negative effect on the corn trade in the UK. However, in Ireland the export of grain continued for some time after 1846 and was further enhanced by the Crimean War of 1854-55. The export of grain was coupled with the import and sale of coal from the UK which was also a very lucrative enterprise. These facts are supported by Mrs Wilkinson4.

Carrick, by virtue of its position on the river Suir, was able to take advantage of this new opportunity. Up to 1846 the Corn Laws subsidised the price of grain which encouraged farmers to grow grain-crops. Corn mills sprung up all over the country and the export of corn to England became increasingly profitable to all classes connected with agriculture. On the Linguan river alone there were 11 mills prior to 1846 – three at the Three Bridges, one at Tinvane (Dowleys), one at Cregg, one at Cregg Bridge (Sadlier’s), two at Newtown (Shee’s & Barry’s). Further up the river were Carrigan’s and Crowley’s mills while the Barnes family had a mill in Grangemokler. On top of this, there were two mills in Carrick town (Dalton’s & Duggan’s) and others in Glenbower and Figlash (Rockett’s). A Teigh Dowley was listed as a land owner in Figlash in 1664 but his relationship with the milling trade is still unknown. Most, but not all these mills were flour mills and in 2011 it is difficult to understand how so many mills in the same area could remain profitable. According to Slater’s Directory in 1846 there were 7 millers in the Carrick area and one of these was the Dowley mill at Tinvane. This would suggest that some eight mills had gone out of business for one reason or another by 1846. The reduction in the number of mills would also have aggravated the food supply problems during the famine period.

The export of grain during the famine period of 1845-1850 was politically unacceptable despite the fact that the people who were starving did not have money to buy it. The grain producers also needed the cash from the export of grain to pay the rent to the landlord.

Leslie J. Dowley

lesdowley@eircom.net

I have once again enjoyed reading the Portlaw story,

my special interest is that Charlotte Newbold married Robert Shaw.

charlotte was in my direct Ancestory,

it may interest you to know that Robert Shaw ,was born to Richard Shaw and Sarah Newbold.

charlotte’s aunty.

the inter marriage of the Shaw’s and Newbold’s amounted to five connections

My grandmother was Sarah Malcolmson, daughter of Thomas Malcolmson of Lurgan, Co. Armagh.

They were descended from Andrew Malcolmson, linen weaver from Scotland. I would love to hear from

anyone who has anything further to add. I have read the Portlaw story with interest! . Eileen Jordan.

brilliant article. Well done on your marvellous research. We both were fascinated with this piece of local history. Best regards to you both. S

Well-written and well-researched. Congratulations.